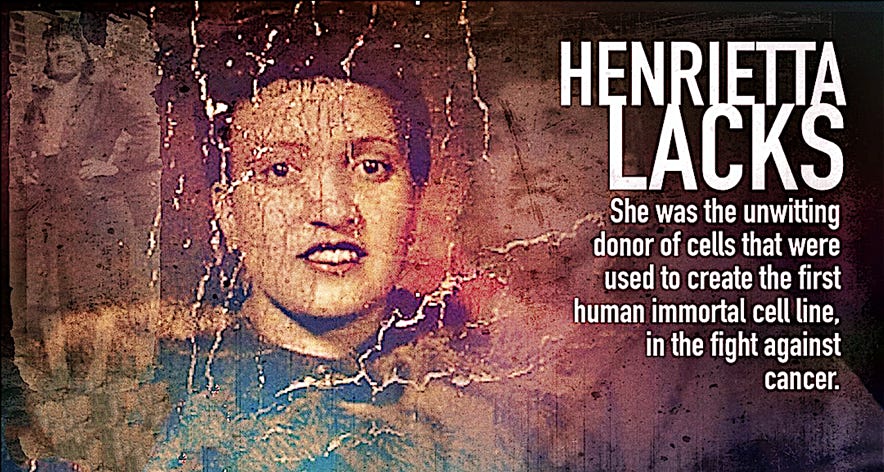

Henrietta Lacks (August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951) was an African American woman who was the unwitting donor of cells from her cancerous tumor that was biopsied during treatment for cervical cancer at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.

These cells were cultured by George Otto Gey to create the first human immortal cell line, now known as the HeLa cell line, which is still used for medical research.

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was diagnosed with cervical cancer and was treated at the segregated Johns Hopkins Hospital with radium tube inserts, a standard treatment at the time. As a matter of routine, samples of her cervix were removed without permission. George Otto Gey (1899-1970), a cancer researcher at Hopkins had been trying for years to study cancer cells, but his task proved difficult because cells died in vitro (outside the body). The sample of cells Henrietta Lacks’s doctor made available to Gey, however, did not die. Instead they continued to divide and multiply. The He-La cell line was born. He-La was a conflagration of Henrietta Lacks.

Permission for doctors to use anyone’s cells or body tissue at that time was traditionally not obtained, especially from patients seeking care in public hospitals. The irony was that Johns Hopkins (1795-1873), an abolitionist and philanthropist, founded the hospital in 1889 to make medical care available to the poor. Informed Consent as a doctrine came into practice in the late 1970s, nearly three decades after Henrietta Lack’s death. The new practice grew out of the embarrassment over WWII Nazi medical experiments and the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment of 1932-1972.

It is believed that, George Gey attempted to protect the privacy of deceased Henrietta Lacks, however some believe his efforts were to intentionally conceal her identity because she was black. Thus the origin of the cells was alleged to have come from Helen Lane or Helen Larson, or even from Austrian-born American actress, Hedy Lamarr (1913-2000). Gey was the consummate professional biologist and used Henrietta Lacks’s cells in the sole interests of finding a cure for cancer.

With no desire for profit, he made the He-La cells available to all interested in biological research, including virologist Jonas Salk (1914-1995). The He-La cell line in turn allowed the discovery of the Salk vaccine which led to the near world-wide eradication of polio.

Lacks was buried in an unmarked grave in the family cemetery in a place called Lackstown in Halifax County, Virginia. Lackstown is the name that was given to the land in Clover, Virginia that was originally owned by white, land- and slave-owning members of the Lacks family before the Civil War. Later generations gave the land to the many black members of the Lacks family who were descendants of African slaves and their white owners.

Lacks's exact burial location is unknown, but the family believes that it is within a few feet of her mother's gravesite, which for decades, was the only one in the family to have been marked with a tombstone.

In 2010, Roland Pattillo of the Morehouse School of Medicine donated a headstone for Lacks after reading Rebecca Skloot's book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. This prompted her family to raise money for a headstone for Elsie Lacks as well, which was dedicated on the same day.

Henrietta Lacks's headstone is shaped like a book and contains an epitaph written by her grandchildren that reads: In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many. Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever. Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family.

Oprah Winfrey stared in a critically acclaimed limited series about Lacks life for HBO, titled “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” in 2017.

Contributors: wikipedia.org, blackpast.org

Copyright Black History Mini Docs Inc. 2026 All Rights Reserved.